< Previous Article

Table of Contents

Next Article >

2023 Ⓒ Boston Intellectual Property Law Association

Keeping Tabs on the TTAB®The Top Ten TTAB Decisions of 2022

Keeping Tabs on the TTAB®

The Top Ten TTAB Decisions of 2022

By John L. Welch, Wolf, Greenfield & Sacks

The Trademark Trial and Appeal Board (“TTAB”) issued more than 600 final decisions and numerous interlocutory rulings in 2022. Thirty-eight of the Board’s opinions were deemed precedential. This article collects ten decisions – listed in no particular order – on a variety of issues that the author finds of importance or interest. It is worth noting that, in keeping with a recent trend in TTAB cases, three of the decisions conclude that the mark in question is unregistrable because it fails to meet the basic requirement that it serve as an indicator of source: either because it “fails to function” as a trademark, or is generic (a sub-set of the failure-to-function concept).

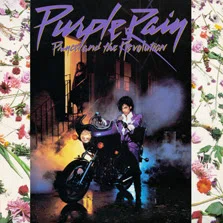

NPG Records, LLC and Paisley Park Enterprises, LLC v. JHO Intellectual Property Holdings LLC, 2022 USPQ2d 770 (TTAB 2022) [precedential].

Finding that the proposed mark PURPLE RAIN for dietary and nutritional supplements falsely suggests a connection with the famous musician and performer Prince, the Board granted opposers’ motion for summary judgment under Section 2(a) of the Trademark Act. The record contained “copious, unrebutted evidence of Prince’s fame among the general consuming public and his unique association with the words PURPLE RAIN.” Evidence of use of PURPLE RAIN by Prince included his album, a movie, and sales of a variety of consumer products under the mark. Survey results showed that 66.3% of the general public recognize PURPLE RAIN as a reference to Prince. The Board agreed with Opposers that “[b]ecause purchasers are accustomed to celebrity licensing, they may presume a connection with a celebrity even though the goods have no relation to the reason for the celebrity’s fame.” “If the applicant’s goods are of a type that consumers would associate . . . in some fashion with a sufficiently famous person or institution, then we may infer that purchasers of the goods or services would be misled into making a false connection with the named party.”

Flame & Wax, Inc. v. Laguna Candles, LLC, 2022 USPQ2d 714 (TTAB 2022) [precedential].

Petitioner Flame & Wax found itself on the short end of the candlestick when the Board denied its petition for cancellation of a registration for the mark LAGUNA CANDLES for “aromatherapy candles; candles; scented candles,” finding that the mark had acquired distinctiveness and therefore was not primarily geographically descriptive of the goods. The Board rejected petitioner’s invocation of the doctrine of claim preclusion based on its earlier successful opposition to respondent’s prior application to register the same mark, finding that this cancellation proceeding involved a different set of transactional facts. In 2013, the TTAB sustained Flame & Wax’s opposition to the same mark for candles on the ground of geographical descriptiveness. Four months later, respondent filed a new application, claiming acquired distinctiveness under Section 2(f). The Board found no case in which an applicant claimed acquired distinctiveness in a second application filed only four months after a successful opposition. Nonetheless, the Board ruled that additional evidence “establish[ed] a recognizable change of circumstances from the time of trial in the Prior Opposition and the time of trial in the cancellation.”

County of Orange, 2022 USPQ2d 733 (TTAB 2022) [precedential].

Every few years, like clockwork, the Board decides a Section 2(b) case. This time it affirmed refusals to register the two proposed marks depicted here, for various governmental services (e.g., maintaining parks and libraries), on the ground that they constitute insignia of a governmental entity, i.e., a “municipality.” The Board rejected the argument that Orange County is not a municipality, as well as the argument that because Orange County already has an “official” seal, these designs cannot be insignia of the county. The Board took judicial notice of a definition of the term “municipality” as a “city, town, or other local political entity with the powers of self government.” Orange County acknowledged that the California Constitution provides that a county may have some such powers: for example, a county may make and enforce local ordinances, sue and be sued, levy and collect taxes, and adopt a charter. The Board therefore concluded that Orange County is a “municipality” for purposes of Section 2(b). The Board further found that the “prominent and repeated display of the proposed Circular Mark to denote traditional government records, functions, and facilities would reasonably lead members of the general public to perceive the proposed mark as an ‘insignia’ of Applicant within the meaning of Section 2(b) of the Trademark Act.”

Vans, Inc. v. Branded, LLC, 2022 USPQ2d 742 (TTAB 2022) [precedential].

In an exhaustive and exhausting opinion, the Board granted petitions to cancel two registrations for the mark OLD SCHOOL for various clothing items, on the ground of abandonment. The Board found that the registrant, despite claiming attempts to sell or license the mark, had discontinued use of the mark with an intent not to resume use. The Board combed through the record evidence in great detail, noting that Branded “failed to introduce any credible documents showing use of the OLD SCHOOL mark to identify clothing or sale of clothing.” Nor was there any evidence of advertising. Branded’s testimony regarding use was unpersuasive because of its inconsistencies, contradictions, and unspecific nature. Petitioner Vans thus established nonuse of the mark since 2008, a period of more than three years and thus prima facie evidence of abandonment. Branded could not prove its intent to resume use of its mark on the basis of its intent to sell the mark, “especially where the evidence that it ‘used’ the mark at all is so vague, inconsistent and unreliable.” “[H]olding a mark with no use, with only an intent to sell the mark at some time in the future, is not proof of present use or intent to resume use.” Indeed, such an intent is evidence of “trafficking in trademarks,” which the Trademark Act seeks to prevent by deeming such an assignment invalid and the involved application or registration void.

In re Erik Brunetti, 2022 USPQ2d 764 (TTAB 2022) [precedential].

Erik Brunetti, famous in the trademark world for knocking the scandalous and immoral provision of Section 2(a) out of the Trademark Act, returned to the TTAB in this battle over the proposed mark FUCK for phone cases, jewelry, bags, and retail store services. The Board affirmed each of four refusals to register on the ground that FUCK fails to function as a trademark, concluding that the word “fuck” is in such widespread use that it does not create the commercial impression of a source indicator, but rather expresses well-recognized, familiar sentiments. The Board rejected Brunetti’s argument that the Supreme Court decision in the FUCT case requires reversal here, and it also rejected his claim of biased treatment by the Board. The failure-to-function refusal was rather straightforward. The evidence established the ubiquity of the word “fuck” in general, and the widespread use of the word for various consumer goods. The Board pointed out that the Supreme Court’s decision in Iancu v. Brunetti concerned only Section 2(a)’s prohibition of registration of marks containing scandalous matter, not the issue of failure-to-function. Applicant Brunetti provided no evidence that “plausibly suggests the USPTO maintains any bias against him . . . or is motivated by his exercise of his first amendment rights.”

In re Integra Biosciences Corp., 2022 USPQ2d 93 (TTAB 2022) [precedential].

Color this applicant TTABlue after the Board nixed its five applications to register various pastel colors used on rack inserts for “disposable pipette tips fitted with a customizable mounting shaft,” finding that the proposed marks are not inherently distinctive, lack acquired distinctiveness under Section 2(f), and are functional under Section 2(e)(5). Although Integra’s products have been commercially successful, it failed to prove that relevant consumers perceive the “Pastel Tints” as trademarks. Furthermore, the Pastel Tints are essential to the use of Integra’s goods and therefore de jure functional, because they ensure that customers use the right tip with the right pipette. That finding alone was fatal, but the Board went on to consider the alternative ground for refusal. The Board found that the Pastel Tints lacked inherent distinctiveness because it is common practice for manufacturers to use matching colors on pipette insert racks and pipette fittings in order to assist the user to associate a pipette tip of a particular size with the correct fitting. As for acquired distinctiveness, the Board applied the CAFC’s Converse factors and concluded that the evidence came up short. Integra provided sales figures, but not in marketplace context. Nor did it provide any advertising figures or proof of “look for” advertising. There was no evidence of intentional copying and no evidence of media coverage. The Board concluded that Integra’s evidence was insufficient to meet its “heavy burden” to prove that consumers recognize the use of the Pastel Tints on insert racks as trademarks.

ARSA Distributing, Inc. v. Salud Natural Mexicana S.A. de C.V., 2022 USPQ2d 887 (TTAB 2022) [precedential].

Finding Applicant Salud’s long period of nonuse of its mark EUCALIN for nutritional supplements to be excusable, the Board dismissed this Section 2(d) opposition because Opposer ARSA Distributing was unable to prove priority. Salud, deemed a Specially Designated Narcotics Trafficker (SDNT), was banned from doing business in the United States from 2008 to 2015. Although it did not resume use of the mark for another seven years, Salud did commence TTAB litigation with ARSA in 2016 regarding ownership of the mark. ARSA established a presumptive prima facie case of abandonment based on Salud’s admitted nonuse of the mark during any three-year period between 2008 and 2015. The Board, however, ruled that Salud’s nonuse during the ban was excusable and further that Salud maintained an intent to resume use after 2016, negating the presumption of abandonment arising from its nonuse during that later period. “This is not a case where Applicant decided to cease use of its mark for business reasons. Rather, Applicant had no choice but to cease use of its mark because its use was prohibited by government sanctions ….” Salud’s “vigorous defense” of this opposition also supported a finding that it maintained an intent to resume use throughout the litigation.

In re Pound Law, LLC, 2022 USPQ2d 1062 (TTAB 2022) [precedential].

Upholding a refusal to register the proposed mark #LAW for legal referral services, the Board found that the term, as used on Applicant Pound Law’s specimens of use, fails to function as a source indicator. Instead, the Board found that the term, a vanity phone number, would be perceived by consumers as merely informational, a means to contact the applicant or its licensee, the Morgan & Morgan law firm. Citing numerous examples from advertising materials of other law firms, the Board found that #LAW is commonly used as a hashtag in the legal field, including by the applicant’s licensee, Morgan & Morgan. Pound Law argued that the Board has long recognized the registrability of mnemonic telephone numbers, but the Board pointed out that the new versions of vanity phone numbers “present a somewhat different situation than traditional alphanumeric numbers.” The different “formation” of these new vanity numbers “impacts perception and distinguishes them” from traditional numbers. Turning to the applicant’s own use of #LAW, multimedia files and website excerpts presented #LAW “as a mnemonic for the telephone number #529, by which prospective clients may contact a lawyer at Morgan & Morgan law firm, not as a source indicator for legal or legal referral services.”

Mystery Ranch, Ltd. v. Terminal Moraine Inc. dba Moraine Sales, 2022 USPQ2d 1151 (TTAB 2022) [precedential].

Section 2(c) inter partes proceedings are as rare as a traffic cop in Boston, but the Board gave the green light to Opposer Mystery Ranch in sustaining this an opposition to registration of the mark DANA DESIGN in the form shown here, for backpacks, hiking equipment, tents, and related goods, on the ground that the mark comprises the name of a living individual, Dana Gleason, without his consent and is therefore barred from registration by Section 2(c) of the Trademark Act. However, the Board rejected Opposer Mystery Ranch, Ltd.’s Section 2(a) false connection claim because the opposed mark is not a close approximation of Mystery Ranch’s name or identity, nor does it point uniquely or unmistakably to Mystery Ranch. The evidence established that, in the field of backpacks and hiking gear, “the name ‘Dana’ is recognized as a nickname for Dana Gleason.” As to the Section 2(a) claim, however, “although consumers associate Dana Gleason and Mystery Ranch . . they are not perceived as each other’s alter ego.” As to the Section 2(c) claim, the Board found Mystery Ranch to be in privity with Dana Gleason and therefore able to assert Gleason’s rights under Section 2(c) to prevent the use of his first name DANA without his written consent, despite the fact that Gleason had assigned his rights in the subject trademark.

In re Jasmin Larian, LLC, 2022 USPQ2d 290 (TTAB 2002) [precedential].

Upholding a refusal to register the product configuration shown here for “handbags,” the Board found the design to be generic and, alternatively, lacking in acquired distinctiveness: “Handbags embodying the proposed mark are so common in the industry that such product design is not capable of indicating source and . . . Applicant’s proposed mark is at best a minor variation thereof.” The evidence included third-party bags sold both before and after the applicant’s first use date, articles about fashion history, Internet postings, and applicant’s own acknowledgement that its design is a copy of a common design. The finding that the proposed mark is generic is an absolute bar to registration on either the Principal or Supplemental Register, but in the interest of completeness, the Board also considered applicant’s Section 2(f) claim. Applying the CAFC’s Converse factors, the Board noted the lack of survey evidence, no showing of “look for” advertising, and sales figures that lacked marketplace context. Furthermore, “[d]istinctiveness is acquired by substantially exclusive and continuous use of the mark in commerce.” The Board found that applicant “failed to demonstrate the ‘substantially exclusive’ use of the proposed mark required by the statute.”