Attacks against priority claims in Europe on the basis of lack of legal entitlement are often raised in post-grant opposition proceedings at the European Patent Office (EPO) and during national litigation. They can also be raised prior to grant, e.g. in third party observations filed during examination proceedings. A strict approach to the issue is applied in Europe.

The most recent decision from the EPO is from the Technical Board of Appeal in case T844/18. The central issue was whether the patentees were legally entitled to claim priority. If not, the patent would be invalid for lack of novelty.

The stakes in this case were high. The patent covered a game-changing development to the “CRISPR” gene editing technology, allowing gene editing to be applied more extensively, particularly to humans.

In their defence, the patentees challenged the EPO’s entire approach to priority entitlement, including whether the EPO has jurisdiction to examine the matter at all. The Board refused to accept any of the patentees’ arguments and determined that they had failed to comply with a fundamental aspect of the law. Consequently, the patent was revoked.

The case does not change the EPO’s established law and practice concerning priority entitlement. However, it provides a sobering reminder of the sometimes draconian consequences of the EPO’s approach and a timely opportunity to reassess best practice for applicants.

In this article a summary of the relevant law is provided together with a more detailed discussion of the T844/18 CRISPR case itself. The “Practical Advice” section at the end of the article provides guidance of this nature. This practical advice can be read either separately or in conjunction with the preceding sections of the article.

The Law in Europe Relating to Priority Entitlement

The right of priority is owned by the applicants

The European Patent Convention (EPC)1 and the Paris Convention (PC)2 provide that the right to claim priority from an earlier patent application is a procedural right owned by the applicant(s) named on that earlier application. This procedural right is separate from the issue of who owns the substantive rights in the invention, e.g. who is entitled ultimately to be granted a patent.

Accordingly, when a priority application is filed two issues arise: (a) who owns the procedural right to claim priority which arises under Article 4 of the Paris Convention; and (b) who is entitled to substantive rights in the invention? Questions under (b) concern who owns the invention, and will necessarily involve a consideration of who invented the relevant subject matter. However, such issues are irrelevant when considering who owns the right to claim priority under question (a). Rather, the right to claim priority vests solely with those named as applicants on the priority application, and/or their successors in title.

This separation between procedural and substantive rights is central to understanding the approach taken in Europe in assessing priority entitlement. It is a very common cause of confusion amongst practitioners from other jurisdictions and where different criteria sometimes apply, for instance in the US.

The right of priority must be owned at the filing date of the European patent application

According to Article 87(1) EPC and Article 4A(1) PC the right of priority can be owned by the applicant’s successor in title. This allows an earlier priority application to be filed by one or more first applicants and a subsequent European patent application to be filed by one or more different applicants. This is common in situations where the earlier application was filed in the US, where one or more inventors are themselves applicants, and where the subsequent application was filed by different applicants, typically one or more companies and/or institutions.

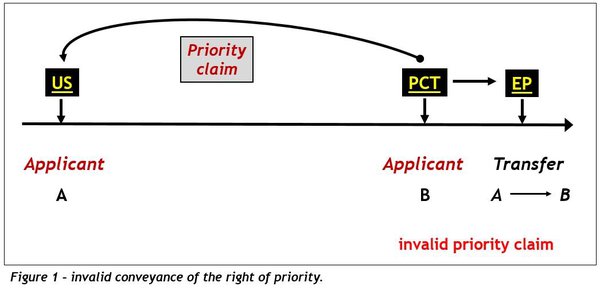

When considering transfers of priority rights, the EPO Boards of Appeal have established that the transfer of the right to claim priority to the applicant(s) named on a priority-claiming European patent application must be complete at the filing date of the European patent application3. The High Court of England and Wales has affirmed the same principle4. Thus, the priority claim will be invalid if the legal instrument which transfers the right to claim priority takes effect only after the European filing date, as depicted in Figure 1 below. Where the European patent application is derived from an international patent application, the relevant date is the filing date of the international application.

The EPO Boards of Appeal have consistently recognised that transfers of intellectual property rights, including the right of priority, should be considered under the relevant national law, or the applicable law as stated in the transfer instrument5. An exception to this principle arose in EPO decision T1201/146. The fact pattern in this case was analogous to that as outlined above in Figure 1. The right of priority was transferred from applicant A to applicant B after the filing date of the subsequent application. The transfer instrument was effective under US law in transferring the right of priority from applicant A to applicant B with retroactive effect (referred to as a nunc pro tunc assignment). Accordingly, under US law the assignment to applicant B would be back-dated to a point in time before the subsequent application was filed. However, in T1201/14 the Board of Appeal refused to acknowledge that the retroactive effect of the assignment under US law provided a remedy for the defect that applicant B was not in possession of the right of priority at the point of filing the European patent application. Quoting from Article 87(1) EPC1, the Board said that the right of priority should be owned by the successor in title “… for the purpose of filing a European patent application in respect of the same invention …” (emphasis added). Thus according to the Board’s reasoning, the applicant for a European patent needs to be in possession of the right of priority at the point in time at which the right of priority is actually exercised.

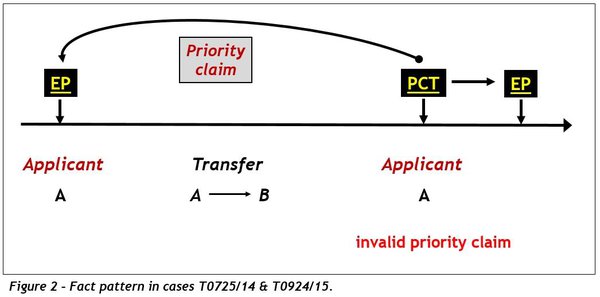

This principle was highlighted in two recent Technical Board of Appeal cases involving the same underlying fact pattern, T725/147 & T924/158, as illustrated in Figure 2 below.

In these cases the priority application had been filed by applicant A. The PCT application had also been filed by applicant A. However, on further investigation it transpired that prior to filing the PCT application, applicant A had transferred its right of priority to B - another legal person. The Board of Appeal accepted that applicant A was not in possession of the right of priority at the PCT filing date and declared the priority claim to be invalid. The patentee requested a correction to the request for grant form, which would have retroactive effect. However the Board refused to allow the correction, since there was insufficient evidence that an error had occurred and that the true intention of the parties had been to list person B as the applicant when the PCT application was filed. These cases highlight that a priority claim may not necessarily be valid merely because the applicant(s) of the earlier and later applications are the same. It is important to understand the full chain of title if any transfers of the right of priority have been made during the 12-month period following the earliest priority date.

The right of priority is owned in a “legal unity” by joint applicants

Any right of priority which is created following the filing of a priority application by two or more joint applicants is owned by the group of applicants in a “legal unity”: the applicants named on the priority application own the right to claim priority together. It therefore follows that all of the applicants named on the priority application must also be named as applicants on the priority-claiming European patent application9, unless they have properly transferred their procedural right to claim priority before the later application is filed.

This principle, which derives from Technical Board of Appeal case T788/0510, has become well established in EPO jurisprudence: the EPO will find the priority claim invalid unless all of the applicants named on the priority application are also named on the later European patent application (absent any transfers of the right to claim priority). The High Court of England and Wales has applied the same principle in finding a priority claim invalid during national litigation proceedings in the UK11. The facts of the case in T788/05 are depicted in Figure 3 below.

To ensure a valid priority claim in this situation, the correct course of action would be to effect a transfer of applicant B’s share in the right of priority to applicant A before the subsequent European patent application is filed. An alternative approach would be to file the subsequent application in the joint names of applicants A and B in the absence of a transfer, thus maintaining legal unity in the right of priority between the two applicants. After the subsequent application is filed a transfer from applicant B to applicant A of all rights in the subsequent application could then be executed and recorded, allowing the subsequent application to proceed in the sole name of applicant A.

Figure 3 above depicts the filing of a direct European patent application claiming priority. However, the same principles apply in a situation where the European patent application derives from a PCT application.

A different scenario was considered by the Technical Board of Appeal in case T1933/1212. In this case a new applicant was listed when filing the subsequent application in addition to the original applicant which had filed the earlier application. No transfer had been executed prior to the filing of the subsequent application. The facts of the case are illustrated in Figure 4 below.

The Board of Appeal in T1933/12 determined that the priority claim in this situation is valid. The right of priority is owned by applicant A, and it is acceptable for applicant A to share its right of priority with applicant B when filing the subsequent application. There is no requirement for applicant A to transfer its right of priority to the combination of joint applicants A and B before filing the subsequent application. This sharing of a right of priority with one or more new applicants has become known as the “joint applicants approach”.

The scenario depicted in Figure 4 can be extended to consider the principle of legal unity amongst original co-applicants, as illustrated in Figure 5 below.

In this scenario the right of priority is owned by applicants A and B in a legal unity, and it is acceptable for these applicants to share their jointly-owned right of priority with applicant C when filing the subsequent application. Legal unity in the right of priority is maintained, since applicants A and B are amongst the group of persons listed as joint applicants for the subsequent application.

Acceptability of the joint applicants approach is confirmed in the Guidelines for Examination in the European Patent Office13.

Facts of the Case in T844/18

In T844/1814 the opponents argued that the patentees had failed to comply with a basic aspect of the law in Europe, the requirement to maintain legal unity between the priority application and the priority-claiming application. According to the opponents, the priority claim was invalid and the claims should lack novelty over intervening publications of the invention in the scientific literature. Figure 6 below shows a simplified fact pattern of the case.

The contested priority claims concerned certain provisional applications filed in the US. These applications were filed with multiple inventors all named as joint applicants. The majority of the original inventor/applicants had properly transferred their shares in the right of priority to their respective institutions before the PCT application was filed. However, one of the original inventor/applicants, Dr Luciano Marraffini (inventor/applicant D in Figure 6), was omitted as a joint applicant of the PCT application, as was the institution to which he had an employment obligation (The Rockefeller University). Dr Marraffini had not assigned his share in the right of priority to any of the institutions listed as applicants on the PCT application from which the relevant European application was derived.

During the opposition proceedings, the opponents argued that the relevant priority claims were invalid because the omission of Dr Marraffini and/or The Rockefeller University as applicants for the PCT application violated the principle of legal unity. The Opposition Division accepted the opponents’ arguments and the patent was revoked. The patentees appealed.

The patentees’ arguments on appeal

On appeal, the patentees argued that the EPO’s entire approach to the assessment of legal entitlement to priority should be overturned. Their arguments were as follows.

1. A right of priority is an item of property. The EPO does not have jurisdiction to determine ownership of a European patent or application15. By analogy, the patentees argued, the EPO should not have jurisdiction to determine ownership of a right of priority. A dispute over the ownership of a right of priority should be resolved by national tribunals in legal proceedings involving only parties having legal standing in the dispute.

2. If the EPO does have jurisdiction, then the principle of legal unity is wrong and should not be followed. According to the patentees, this principle undermines the true intention of the Paris Convention as it prevents applicants from exercising their right of priority independently of other joint applicants. According to the patentees, in the relevant provisions of the Paris Convention and the European Patent Convention the language “any person” who can exercise a right of priority should be interpreted to mean any one person. This would mean that any one of the original applicants, or their successors in title, could exercise the right of priority independently of any of the other joint applicants, as depicted in Figure 7 below.

3. Even if the principle of legal unity is applicable, then the patentees contended that it is still fulfilled when considering the specific facts of the case. This contention relied on two positions, as follows.

First, the question of who is accorded “applicant” status for a priority application should be decided under the law of the jurisdiction in which that application was filed. In this case the priority applications were filed in the US, and so US law should apply to the question of to what extent Dr Marraffini (inventor D in the Figures) owned part of the priority rights created by the priority applications.

Second, essentially the patentees argued that the answer to this question needed to take into account the specific subject matter that was disclosed in the priority-claiming PCT application. According to the patentees, any subject matter in the priority applications to which Dr Marraffini contributed (i.e., “invention 2”) had been deleted before the PCT application was filed. Dr Marraffini did not contribute to the subject matter that was retained in the PCT application (i.e., “invention 1”). Hence, neither Dr Marraffini nor his institution owned any part in the right to claim priority for the subject matter that was actually disclosed and claimed in the priority-claiming PCT application. Therefore, their omission from the listing of applicants in the priority-claiming application allegedly did not contravene the requirement for legal unity. The patentees’ third argument is depicted in Figure 8 below.

The Board’s decision – no change to the law

The Board of Appeal rejected all of the patentees’ arguments and dismissed the appeal. The omission of Dr Marraffini and/or The Rockefeller University from the list of PCT applicants proved fatal for the validity of the contested priority claims. The Board consequently held that the claimed invention lacked novelty over the intervening prior art and the patent was revoked.

The decision affirms the EPO’s existing case law and practice, which can be summarised as follows.

- EPO Examining Divisions, Opposition Divisions and Boards of Appeal are legally competent to examine entitlement to priority.

- The principle of legal unity in joint ownership of a right of priority continues to apply. Joint applicants of a priority application cannot be considered to each own a right of priority which can be exercised independently of the other joint applicants in the absence of a transfer of rights.

- The question of who is a “person” who owns a right of priority, i.e. who is an applicant for the priority application, will not be examined in accordance with national law. The European Patent Convention and the Paris Convention are to be applied.

- The filing of an earlier application disclosing multiple inventions does not give rise to multiple procedural rights of priority, each one directed to a separate invention and which can be owned by different applicants or groups of applicants. Rather, a single procedural right is created by the filing of the earlier application and that is held jointly by all of the applicants (this being a consequence of the separation between procedural and substantive rights that is applied under EPO practice).

- Assessment of legal entitlement requires: (a) a determination of which persons were applicants of the priority application, irrespective of issues relating to inventorship; (b) whether the requirement of legal unity is satisfied, if joint applicants are involved; and (c) whether the applicant(s) of the subsequent European patent application owned the right of priority at the filing date. In the analysis under (c), any transfer of ownership, e.g. via a transfer instrument such as an assignment or employment contract, will continue to be examined under the law applicable to the transfer instrument.

Practical Advice on Safeguarding Priority Claims in Europe

In view of T844/18 it is possible to re-affirm a number of best-practice principles that can be observed to mitigate against attacks on legal entitlement to priority in Europe. As already discussed, an overarching philosophy linking these principles is that the right to claim priority is a purely procedural right created by the filing of a priority application, which under EPO practice is considered separately from the question of substantive ownership of the subject matter disclosed in the application.

- Where a priority application is filed by joint applicants, all applicants will own the right of priority as a combined group. Implications of this include:

a. The same group of joint applicants should be listed as joint applicants for the subsequent European patent application in order to maintain legal unity. b. Alternatively, if the configuration of joint applicants as between the earlier application and the subsequent application is to be different, transfers of the right of priority must be effected so that the legal unity is maintained amongst the group of joint applicants who file the subsequent application. c. Alternatively still, if the subsequent application is to be filed by a single applicant, all separately-owned shares in the right of priority should be transferred to and consolidated with the sole applicant. d. Any and all transfers of ownership in the right of priority must be effected before the filing date of the priority-claiming application. Back-dating a transfer is unlikely to be accepted, even when the relevant national law permits such transfer agreements to be back-dated16. e. If there is any doubt that a transfer of ownership from one person to another has been perfected before filing the European patent application, then both persons should be listed as applicants. Extending this principle, all joint applicants of the priority application as well as their purported successors in title could be listed as applicants for the European patent application if there is doubt in the chain of title. After an application is filed with such an extended list of applicants, appropriate transfer documents can be prepared to vest rights in the intended parties.

- Any transfer of ownership in a right of priority should preferably be effected via a written assignment signed by all parties. The document does not need to be submitted to the EPO as a filing formality. However, evidence of a transfer will be needed if the priority claim is challenged. Case law of the EPO Boards of Appeal17 and the High Court of England and Wales18 has affirmed that a transfer can in certain circumstances be recognised in the absence of a formal written assignment. Nevertheless, since evidence of the transfer may be needed the following steps are recommended:

a. that a written assignment is executed before the priority-claiming application is filed; b. that the assignment instrument is signed by both the assignor(s) and the assignee(s); c. that the assignment instrument identifies the earlier application by reference to the jurisdiction in which it was filed, the application number and the date of filing; d. that the assignment instrument makes specific reference to the transfer of “the right to claim priority” from the earlier application; and e. that the assignment instrument states the applicable law by which it should be interpreted and governed, and that the instrument complies with the applicable law when executed.

Summary

The decision of the Technical Board of Appeal in T0844/18 has clarified a number of aspects concerning legal entitlement to priority in Europe. However, it should be stressed that this remains an evolving area of the law. At the hearing before the Board of Appeal in T0844/18 there was a heated debate between the parties as to whether questions of law should be referred to the EPO’s Enlarged Board of Appeal. A referral was refused in that case. However, it cannot be ruled out that such a referral may be made in the future. At the very least, further developments in the law are anticipated, and consequently the issue of legal entitlement to priority in Europe is likely to remain a hot topic for the foreseeable future.

1 J19/87Article 87(1) EPC.

2 Article 4A(1) PC.

3 E.g. , T62/05 and T1201/14

4 Edwards Lifesciences AG and Cook Biotech Inc. [2009] EWHC 1304

5 E.g. J19/87, T1008/96, T1201/14, T205/14, T517/14

6 T1201/14.

7 T725/14.

8 T924/15.

9 References to a “European patent application” include applications filed directly at the European Patent Office and international (PCT) applications designating EP

10 T788/05.

11 Edwards Lifesciences AG and Cook Biotech Inc. [2009] EWHC 1304.

12 T1933/12.

13 Guidelines for Examination, Part A, Chapter III, 6.1, March 2021 edition.

14 T844/18.

15 Article 60(3) EPC.

16 T1201/14.

17 E.g. J19/87, T0205/14, T0517/14

18 KCI Licensing Inc. & Others v Smith & Nephew Plc & Others [2010] EWHC 1487.